WATCH NOW

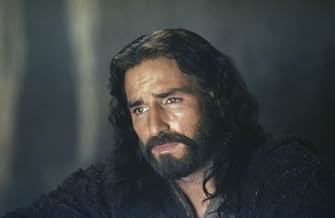

The movie that best exhibits the portrayal of “passion” in its title is none other than “The Passion of The Christ,” directed by Mel Gibson. Jesus of Nazareth was deeply tortured not just physically but also mentally and emotionally. The term ‘passion’ is often interpreted as romance but its origin derives from suffering and pain. In simpler terms, the willingness to suffer for the greater good.

This movie runs for 126 minutes and in my estimation, at least 100 minutes is exclusively dedicated to illustrating the suffering and death of Jesus. This is the most vicious, gruesome film I have ever watched.

When assessing a film, I try to see it from the creator’s perspective rather than my own. In this case, Mel Gibson wanted to make clear and graphic the price that Jesus paid (as Christians believe) when he died for our sins. As a Catholic, you probably know the waypoints. The script has been shaped not so much by the Gospels but by the 14 Stations of the Cross. As an altar boy serving during the Stations on Friday nights during Lent, I was taught to reflect upon Christ’s endurance, and I recall the chants that were sung by the priest as he moved from one station to another:

At the Cross, her station keeping …

Stood the mournful Mother weeping …

Close to Jesus to the last.

As We altar boys, this was not particularly a moving spiritual moment. He suffered, he died, he resurrected, we were saved, and for the love of God let’s hope we make it home in time to watch the Illinois basketball game. What Gibson has given to me, for the first time in his life, is an instinctive view of what the Passion was. That his film is shallow in the context of the surrounding message — that we receive only a handful of fleeting references to the teachings of Jesus — is, I suppose, not the issue. It is not a sermon or a homily, but rather a visualization of the main event of the Christian religion. Accept it or don’t.

A critic I admire, David Ansen, seems to think Gibson has crossed a line in his work. In Newsweek, he writes, “The unending gore is counterproductive… Rather than being awed by the sacrifice or moved by the suffering, I was emotionally abused by a filmmaker trying to punish, for who knows what sins.”

I quote Ansen because from my perspective it appears that a significant portion of the audience will enter the theater during a reverent or pious state, and leave completely unsettled. This is an anticipated response to the film. And to fully appreciate the depiction of Jesus, you’re going to need to brace yourself for the sound of whippings, bane, flaying, beatings, bone-crunching, screams of agony, blood, the violence of sadistic centurions, and the rivulets of blood that crisscross Jesus’ body. A number of people may choose to not watch the film until the very end.

Laudable as it is, The Passion of the Christ is unique in more ways than one. I will never forget those 1950s Hollywood bibles movies that I saw as a child, which seemed to be a living reproduction of model figurines. My jaw dropped when Time magazine described how Jeffrey Hunter, who played Jesus in “King of Kings” (1961), had his armpit hair removed. (This is not Hunter’s fault; in fact, the preview audience for the film was so angry with Jesus’s meaty chest that the Crucifixion scene had to be reshot.)

Gibson’s film, if nothing else, will shatter the custom of representing Christ and his followers as well-groomed clerks. They were destitute in every sense of the word. This stems from the debate I had with Scorsese about “The Last Temptation of Christ”, where I battled alongside Michael Medved in front of a Christian college. One spectator asked me whether I cut their hair because they were so dirty.

This part of the world in biblical times was occupied by the Roman Empire. While Jesus’ message was controversial and radical for the Romans, it equally unsettled the Jewish priests who were set to lose power. Thus, both sides suffered equally with his teachings.

In one of the scenes, Jesus’ death is left to be judged by Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor while Caiaphas, the Jewish high priest, gets to decide if Christianity will even be a thing. In an era depopulating of powerful figures, both of these assistants to power see Jesus as a dangerous man and while they don’t mind him being killed, they need to mind not drawing too much attention in the process.

Caiaphas doesn’t kill Jesus unlike how a popular interpretation of the gospels paints him, which is a shame since that archetype robs him of his humanity. In my favorite parts of the film, we see a gentler side to Caiaphas – he brings up the argument, ‘I do believe one man could die,’ but is hastily interrupted before he can finish why, “to save the nation.”

If Gibson had incorporated this line, as he did with Pilate, it could have further showcased the parallels between Caiaphas and Pilate and perhaps lessened the concern of anti-Semitism. “Gibbons’ anti-Semitism claims seem justifiable for the reason that: “The feud does seem anti-Semitic for several reasons, such as the more dramatic aspects flowing freely without skipping, even for the latter half of the Jesus-Pilate conflict”.” My understanding is that his film, while not anti-Semitic, captures the broader spectrum of activities of the depicted Jewish characters, mostly positively. Those Jews who usurp the power and authority of the priesthood to wish for the death of Christ have other, more political and sociological issues to grapple with. Their lots explain why there seem to be so many members of the Catholic diocese and other high-ranking ecclesiastical in command who do so much to promote undisciplined priests who bring their religion into disrepute. The other Jews observed in the film are portrayed in a favorable light.

I am convinced that a rational individual would take the trouble to think through how in this story based on a Jewish country, there are so many people and each has some motives, either good or bad. They all serve individually without serving their religion. This story includes a Jew who tried no less than to supplant the established religion and put himself as the Messiah. His Jewish counterparts did not look at him favorably and for good reasons, but at the same time, he did manage to get support in the form of disciples and later church members, all of whom were Jews. The libel that Jews “killed Christ” is a systematic example of a wrong interpretation and teaching. Jesus came as man and came down to this planet for the sole purpose of suffering and dying to atone for our sins. No race, man, priest, politician, or even an executioner was responsible for killing Jesus – they didn’t. He died because it was the will of God. As much as it stabs the truth, there’s no reason to deny that throughout history, certain Christian churches have poisoned the world by practicing the sin of anti-Semitism. In doing so, they suppressed their very core beliefs.

This talk might be out of place to people who are not interested in the theology of the movie, but rather the movie itself. However, “The Passion of the Christ,” is dependent, like no other film I can think of, on theological reflection. Gibson has not produced what anyone would describe as “commercial,” and if it makes millions, it certainly will not be because people found it enjoyable. Rather, is a personal message movie of the most extreme sort, attempting to reenact experiences of profound significance to Gibson. The movie maker has sacrificed his talent and wealth for his faith and conviction, which is a rare occurrence in the modern day.

What do you think, “good” or “great?” I am sure their reaction (visceral, theological, artistic) will be different. To emphasize, I was moved by the depth of feeling, by the skill of the actors and technicians, by the desire to see this project through no matter what. To talk about individual performances, like that of James Caviezel, who heroically portrayed the great ordeal, is nearly beside the point. This isn’t a movie about performances, which are powerful, or technique, which is incredible, or about cinematography, although it is done by Caleb Deschanel who paints with the eyes of an artist, or music. Still, John Debney supports the content without distracting from it.

An idea is what separates a film from another. An idea that is within The Passion, if Christianity is to make any sense. Gibson has imprinted his idea with a singleminded fervor. Many people will disagree. Some will agree but will be taken aback by the graphic treatment. I am not religious in the sense of a long-ago altar boy, but I can respond to the power of belief, and when I find it in a film, I must respect it.

I mentioned the movie is the most violent I have ever seen, and it likely will be for you too. This is not a critique, instead, it is an observation. It is problematic to younger viewers, but for older viewers who can endure it, it works powerfully. The R rating by MPAA is solid evidence that the organization either will never hand out an NC-17 rating for violence alone, or they were too scared of the subject. Had it been anyone rather than Jesus on that cross, I have a gut feeling that NC-17 would have been automatic.

For More Movies Like The Passion of the Christ Visit on 123Movies.

Also Watch for more movies like: 123movies.