WATCH NOW

It is not so much about the quantity of effort put into 2001: A Space Odyssey by Stanley Kubrick, but rather the quality of his efforts. This comes from a place of utter artistic confidence, knowing with certainty that one can capture our attention through sheer brilliance alone. Each scene has been stripped down to the core and left onscreen just long enough for the audience to truly immerse in it. Unlike other films of its genre, 2001 does not aspire to enthrall us, but rather leave us spellbound.

From the start, Kubrick had an enormous impact, much of which can be credited to the soundtrack. He originally hired Alex North for an original score, but North was pasted which would work perfectly as a temporary track while Kubrick edited the film, but the set was not much better than what was dubbed to be “the original version.” This was the most impactful decision he made. Shoulders: possibly wrong for 2001 would have been different. Most scores attempt to underline actions; the emotion cues. North’s score, which exists solely on a recording, is well done in film composition but would have like all scores tried to underline the action however, the music North has provided does not accompany the action. It uplifts and most importantly takes center stage. It acts as a serious remedy to everything visually stimulating to the eyes.

Let’s look at two case studies. The waltz “Blue Danube” by Johann Strauss, which plays when the space shuttle connects to the station, is purposely slow and so is the action. Such a docking would need to take place with caution (as we know now), but other directors could have overestimated the pace of the space ballet and could have fueled it up with exciting music, which would have been a mistake.

We are given the cue to think about the action, to float around in space, and to observe it. The music is familiar to us. It continues as it is supposed to. And so, in a strange way, the space equipment is moving slowly, keeping the tempo of the waltz. At the same time, there is an exaltation in the music that helps us feel the grandeur of the event.

Now, consider Kubrick’s famous use of Richard Strauss’ choice of Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Inspired by the words of Nietzsche, the five bold opening notes embody the ascension of man into spheres reserved for the gods. The tone is cold, frightening, and magnificent.

In the 1968 film, one of the themes of the music is related to the entry of a man into the universe at the opening of the movie, and the final emergence of a new level of consciousness through the Star Child at the end. Popularized classical music is, in most cases, absurd. Who can hear the “William Tell Overture” without picturing the Lone Ranger on television? More than most other filmmakers, Kubrick has broadened the role of music by associating it with his imagery. A modern symphony would be out of style with fame and popularity, as classical music is most commonly paired for commerce, entertainment, promotions, marketing, and other games, and makes it lose its touch of sophistication and stillness.

Back in 1968, I was able to watch the premiere of the film at the Pantages Theater. Describing the audience’s anticipation is almost impossible. Kubrick had worked on the film for several years in secret, and the audience knew that he was working with Arthur C. Clarke, special effects innovator Douglas Trumbull, and other consultants who helped him flesh out his future vision, from space station designs to business logos. To avoid flying, Kubrick set sail on the Queen Elizabeth from England, continuing to edit while onboard. He then continued working during a cross-country train trip. Now, he finally had a finished product.

Describing that first screening as a debacle would be inaccurate. For those who stuck around until the end, many would argue that it was one of the greatest films ever made. But not everyone was so optimistic. Rock Hudson angrily stormed down the aisle, shouting, “Will someone tell me what the hell this is about?” A lot of people walked out, and there was some agitation because of the film’s slow pacing. (Kubrick cut about 17 minutes, including a scene where a pod repeated another pod’s sequence).

The film’s storyline was unclear while providing little amusement to the watchers. The final scene where the astronaut is placed in a bedroom somewhere beyond Jupiter is unsettling. The overnight Hollywood verdict was that Kubrick was off the rails in claiming that the movie had become too obsessed with its effects and set pieces.

In reality, he was making a philosophical point about man’s place in the cosmos using images as those who had come before him used words, music, or prayer. He had made it so that we do not merely partake in it as entertainment devoid of deeper consideration, like in a conventional science-fiction film, but rather as a philosopher and ponder over it.

The movie consists of different movements. In the first part, the prehistoric apes discover that bones can be wielded as tools when facing a mysterious black monolith. I feel that the monolith, which was indubitably made by other beings, prompted the ape’s brain to realize that it could be used to shape the objects around him.

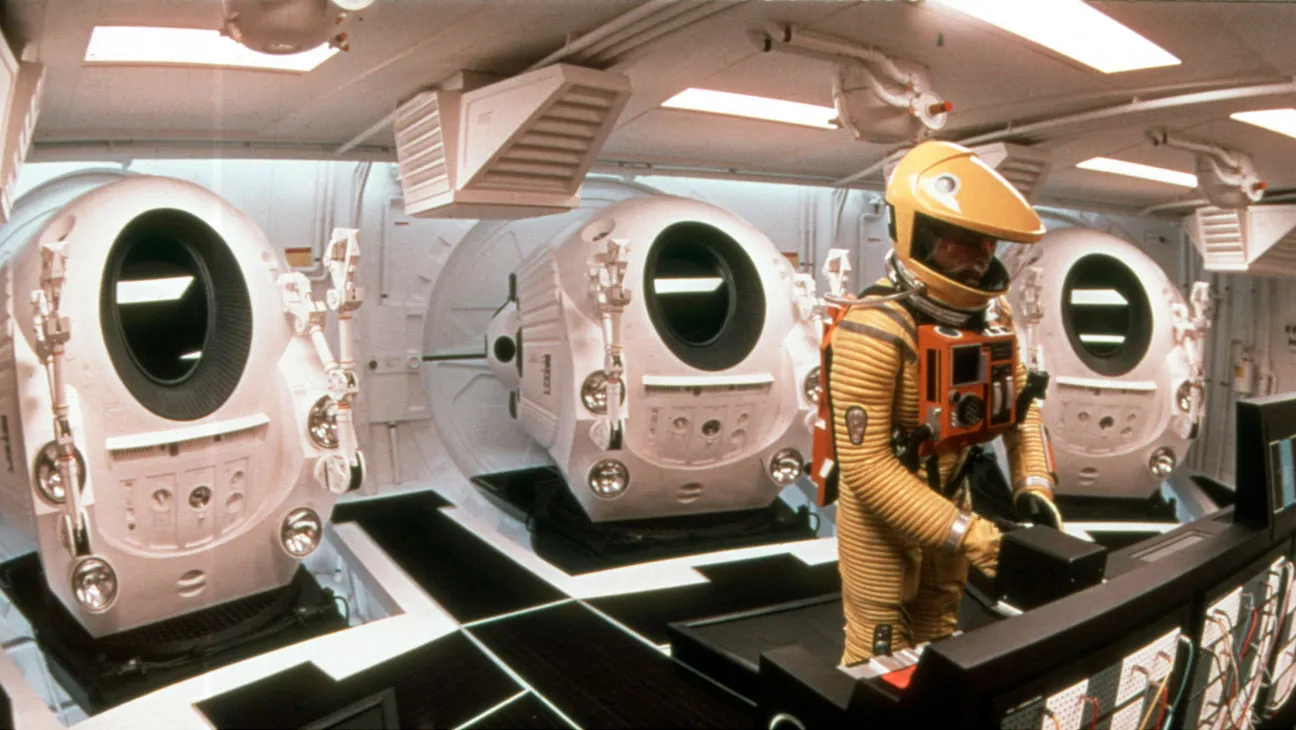

In an instant, we are introduced to Dr. Heywood Floyd (William Sylvester) who is traveling to a space station and towards the moon. This has been dubbed the longest flash-forward in the history of the cinema. This segment is purposefully anti-chronological there are no hasty spoken passages to explain his purpose. Instead, Kubrick depicts the little details of the flight; the design of the cabin, the specifics of the in-flight service, and even the effects of zero gravity.

If the audience was restless, they were surely quieted by the wonderous visuals during the docking sequence. The sight of having familiar brands on board alongside participating in a mystifying conference with scientists across various nations makes for fascinating watching. The videophones and the zero-gravity toilets are intriguing gimmicks as well.

The moon sequence is as real-looking as the actual moon landing and is an adaptation of the film’s first sequence. Man, just like the apes, comes across a monolith, which draws similar conclusions. This was created by someone. And just like the first monolith leading to the discovery of tools, the second monolith leads to the most sophisticated device crafted by man, which is also known as the spaceship Discovery, a tool more powerful than a mere “tool.” In partnership with the computer onboard named HAL 9000, which acts as the man’s artificial intelligence aide, all of this is possible.

The routine of life aboard the Discovery is a repetitive one dissected by exercise, maintenance, and chess against HAL. The astronauts only have some interest when they are in jeopardy of fearing that HAL has malfunctioned they attempt to somehow outsmart HAL, who has been conditioned to think, “This mission poses issues that I will not allow you to impair.” The men trying to have a private conversation inside some space capsule while HAL lipreads them is one of the great moments in cinema. The way Kubrick refrains from fully showing what HAL is doing is incredible: He shows it but doesn’t overemphasize. He makes it clear but does not dwell on it. He gives us enough credit.

Next is the iconic “Stargate” scene, where astronaut Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) goes through a light and sound journey. He moves through a wormhole into a different, indescribable dimension. At the end of the journey, he is in a pleasant bedroom suite where he ages peacefully, having his meals in silence, taking naps, and living the life (I think) of a zoo animal put in a comfortable setting. And then there comes the Star Child.

The narrative does not delve into detail about the other advanced civilizations that supposedly created the monoliths and placed the star gate alongside the bedroom. “2001” lore infers that both Kubrick and Clarke attempted to create believable aliens but failed to do so. That is all for the best. The alien race is instead better imagined to be existing in negative spaces. We can react more strongly towards their invisible essence rather than any real representation.

As with most of Kubrick’s works, “2001: A Space Odyssey” should appeal to the side of you that appreciates silence because it is, in many ways, a silent film. The conversations present can largely be displayed with title cards. Much of the dialogue serves only for the sake of appearing as if people are talking to each other (this applies to the conference at the space station). Ironically, the line filled with the most emotion comes from HAL, when it begs for its ‘life’ and sings Daisy. HAL is, after all, simply a machine.

Even in the most sophisticated of films, the special effects come off as disingenuous and overblown. In “2001: A Space Odyssey” however, the effects are perfected. They seem much more believable, functioning seamlessly with the rest of the film, rather than being distracting and overly polished. Instead, the visuals and the music are a form of special effects. Even decades down the line, viewers are not dimmed in any crucial aspect, and while the capability of doing special effects for a computer era has become more dynamic, Trumbull’s precision seems to trump it all. It almost seems more believable, especially when compared to the complex special effects in later movies.

Very few films are transcendent and stimulate our minds like music or prayer or are accompanied by a context that is unearthly. Every other film revolves around people set on achieving something and, after going through something comedic or dramatic, achieving it. ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ has no set objectives, only a quest or a drive. It does not anchor its effects on particular points of the plot, nor does it expect us to sympathize with Dave Bowman or any other actor. It relays We became men when we learned to think. We have the tools to grasp where we exist and who we are we need to evolve further to understand the truth, that we do not reside on a planet but among stars, and that we’re not flesh, but intelligence.

To watch more movies like A Space Odyssey (1968) visit 123Movies.

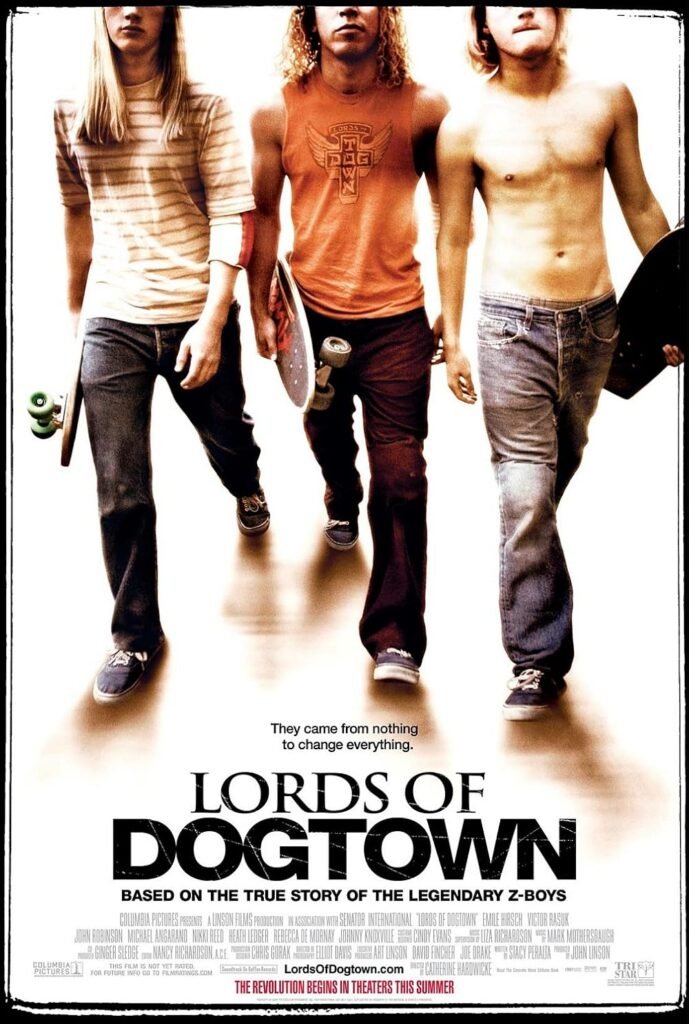

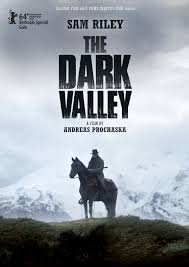

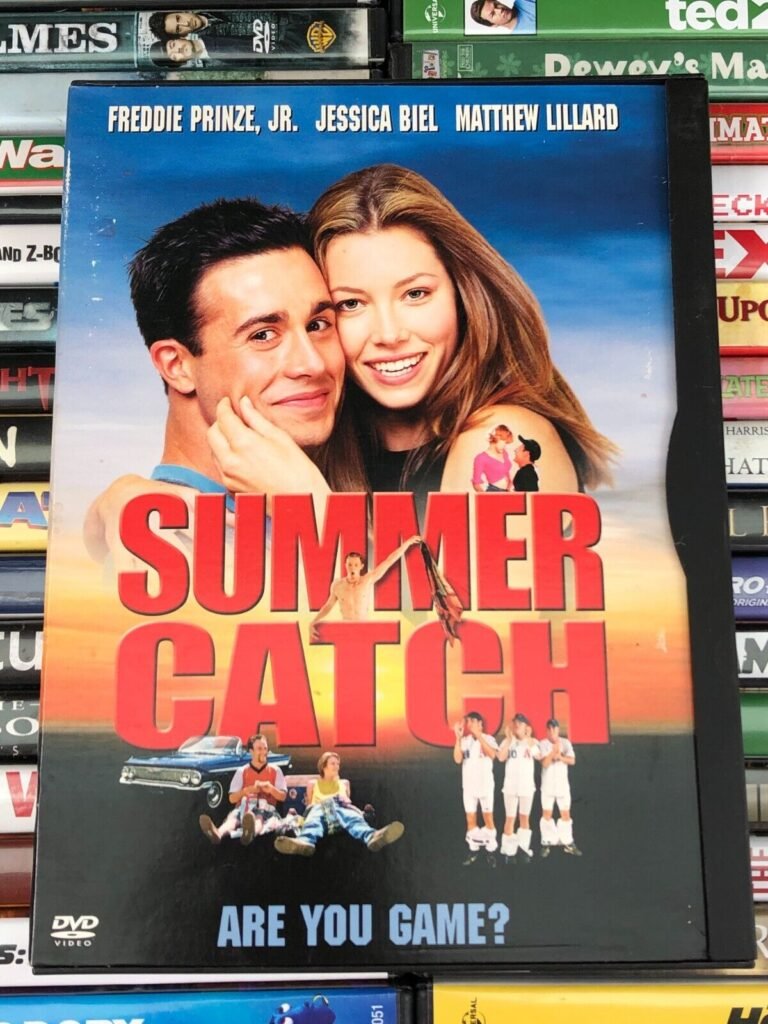

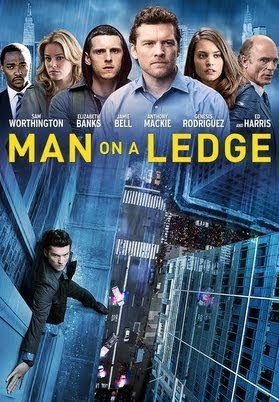

Also Watch for more movies like: